Colorado is gearing up to fight for water rights as the Colorado River stalemate continues

The state’s lead negotiator and attorney general field lawmakers’ questions on what comes next if negotiations fail over the operation of the basin’s two largest reservoirs

Chris Dillmann/Vail Daily

As Colorado continues to negotiate with the seven Colorado River basin states on the post-2026 operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the state’s attorney general and lead negotiator are ready for a legal battle if the states continue to clash.

“If it comes to a fight, we will be ready,” said Becky Mitchell, the Colorado River commissioner, who represents the state on the Upper Colorado River Commission, at the Friday, Jan. 23 SMART Act hearing for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, where the agency provided its annual update on priorities and programs to lawmakers.

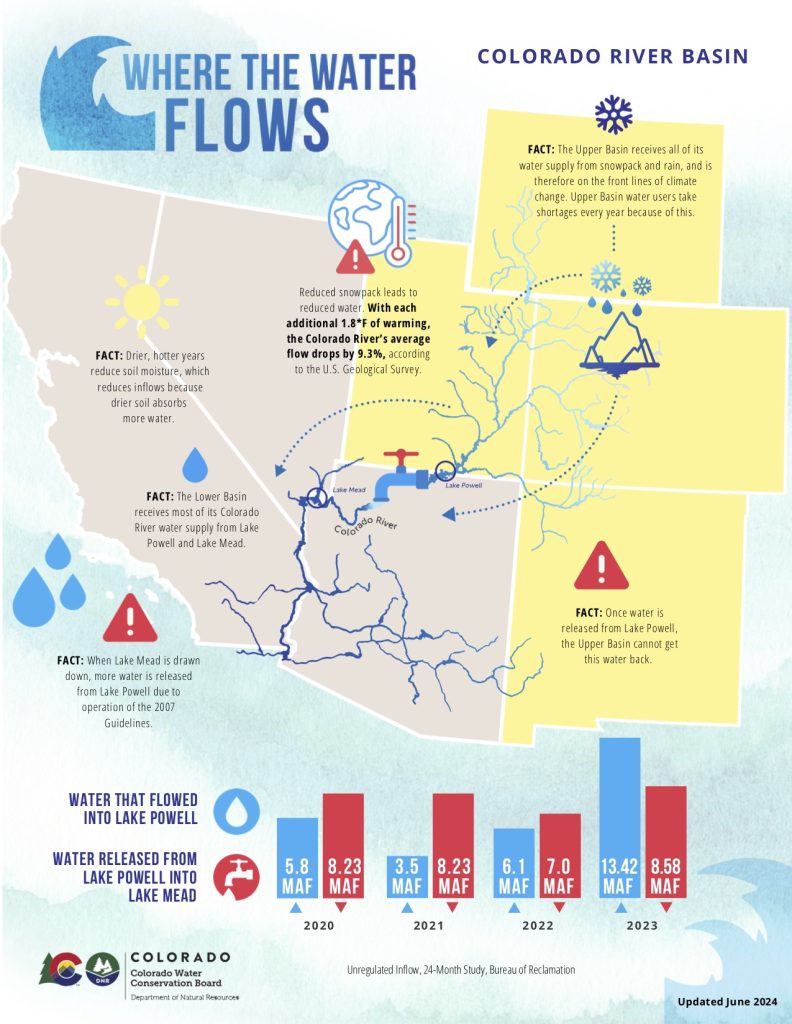

After two years of back and forth, Colorado River basin states remain deadlocked, unable to agree on the guidelines for how Lake Powell and Lake Mead should operate beyond 2026. The operations of these two critical reservoirs have widespread implications for the approximately 40 million people, seven states, two counties and 30 tribal nations that rely on the river.

In Colorado, the Colorado River and its tributaries provide water to around 60% of the state’s population.

“We developed priorities that continue to serve as my north star as we negotiate these post-2026 operational guidelines,” Mitchell said. “The most important of these priorities is to protect Colorado water users. This means that our already struggling water users and reservoirs cannot be used to solve the problem of overuse in the lower basin.”

Despite disagreements over how the reservoirs should operate in an uncertain future, reaching a consensus between the seven Colorado River basin states remains the objective for all involved, but time is ticking.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation — which manages Lake Powell and Lake Mead — has given the states until Feb. 14 to reach an agreement before the federal agency steps in and makes the decision itself.

Mitchell told lawmakers that she was still “optimistic” about reaching a consensus by the deadline, adding that she will “sit in the room with the full intent to negotiate,” as long as there are “willing parties.”

“Folks should start worrying when I’m no longer in the room,” she said. “I will, 100%, be focused on a deal until there’s not a deal to be had.”

In the Colorado Department of Law’s SMART Act hearing on Jan. 20, responding to a question from Sen. Dylan Roberts, D-Frisco, Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser said that if a deal isn’t reached, litigation is a likely outcome.

“If we can’t get a deal — and I’m committed to not getting a bad deal just to get a deal — you’re 100% right, Senator, we’ll be in litigation,” he said. “We’re ready for it. We will stand by our rights, and if and when we can get a reasonable deal, based in reality, I’m for it. But if we can’t, then we will be falling back on our rights we have under this 1922 compact.”

As the states continue negotiations, the Bureau of Reclamation is forging ahead with the necessary steps to make the call itself. The federal agency released a draft environmental impact statement earlier this month outlining five alternatives, which Mitchell likened to a “menu” of options, with the final agreement incorporating elements of multiple alternatives.

Each option offers differing methods for how the Bureau of Reclamation will operate Lake Powell and Lake Mead, particularly under low reservoir conditions; allocate, reduce or increase annual allocations for consumptive use of water from Lake Mead to the lower basin states; store and deliver water that has been saved through conservation efforts; manage and deliver surplus water; manage activities and make cuts above Lake Powell; and more.

Colorado intends to submit comments on the draft and alternatives by the March 2 deadline, Mitchell said.

What are the basin states disagreeing about?

The allocation of the Colorado River’s water supply is driven by a 1922 compact agreement, which divided the river into an upper and lower basin.

Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming comprise the upper basin. These states rely predominantly on snowpack for their water supply, which is divided based on a 1948 upper basin compact. The lower basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — rely on releases from Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

The operational guidelines that govern the two Colorado River reservoirs were set in 2007 and will expire this year. It is not the original compact, but these guidelines that the states have been negotiating for over two years.

“The current operational guidelines are demand-driven, and have allowed downstream demands to drive the system into the crisis that we are facing today, coupled with historically poor hydrologic conditions,” Mitchell said. “This has led to the Bureau of Reclamation looking upstream, even into Colorado for solutions.”

As of Jan. 25, Lake Powell and Lake Mead were 27% and 34% full, respectively.

The draft environmental impact statement from the Bureau reported that the anticipation of drier future conditions makes managing the reservoirs’ storage even more difficult in an already “complex basin.”

Any agreement must balance “the potentially profound impacts of water-delivery reductions with the need to maintain reservoir storage,” the draft states.

The geographic and hydrological differences between the upper and lower basin states are a significant reason why the states are clashing in negotiations, according to Colorado stakeholders.

“We don’t have such reservoirs, so when there’s less water, we use less water,” Weiser said.

At the Department of Natural Resources hearing, Sen. Marc Catlin, R-Montrose, likened the lower basin’s situation to living under a bucket.

“If you live under a bucket like they do, all you gotta do is pick up the phone and ask for more, and they’ve been able to get it,” Catlin said, adding that on the Western Slope, people live within the means of the river.

“Where we were at, and all of us in this room know, what’s not happening this winter is gonna tell on us this summer,” he said, as the state faces historically low snowpack and worsening drought conditions.

One of the main disagreements throughout negotiations has been who should be making cuts to water use. The Lower Basin states have advocated for basin-wide water use reductions. The Upper Basin states, however, have pushed back on the idea, claiming they already face natural water shortages driven primarily by the ups and downs of snowpack. The upper division has proposed restoring balance between water supply and demand.

“The reason it’s hard to get a deal is you need two parties living in reality,” Weiser said. “If one party is living in La La Land, you’re not gonna get a deal.”

When asked by Catlin whether the lower basin states understood the upper basin states’ relationship between water use and what Mother Nature supplies, Mitchell said she believed the lower states had a “willful and deliberate misunderstanding.”

“Because if you acknowledge it, you have to address it,” she said. “Whether they understand or not what living within the means of the river is, I believe they are willing to inflict pain on anywhere else but themselves.”

Mitchell said that she believes, “a consensus approach must be based on available supply and variable hydrology.”

“When we talk about the goals and the projections and the alternatives, we know that there were some in there that are physically impossible,” Mitchell said. “And there is a responsibility by the federal government to operate those reservoirs in a way that doesn’t crash the entire American West. That is the battle that we are in right now.”

There’s also a responsibility of the upper basin states to bring solutions to the table and bear some of the responsibility, she added.

“We have proactively put things on the table to do just that, including releases from those reservoirs under certain conditions, as well as conservation activities in coordination with the upper division states,” she added.

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

As a Summit Daily News reader, you make our work possible.

Summit Daily is embarking on a multiyear project to digitize its archives going back to 1989 and make them available to the public in partnership with the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection. The full project is expected to cost about $165,000. All donations made in 2023 will go directly toward this project.

Every contribution, no matter the size, will make a difference.