Which waters deserve protection? Federal proposal and Colorado disagree

The U.S. Army Corps and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are proposing a new definition of “Waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act

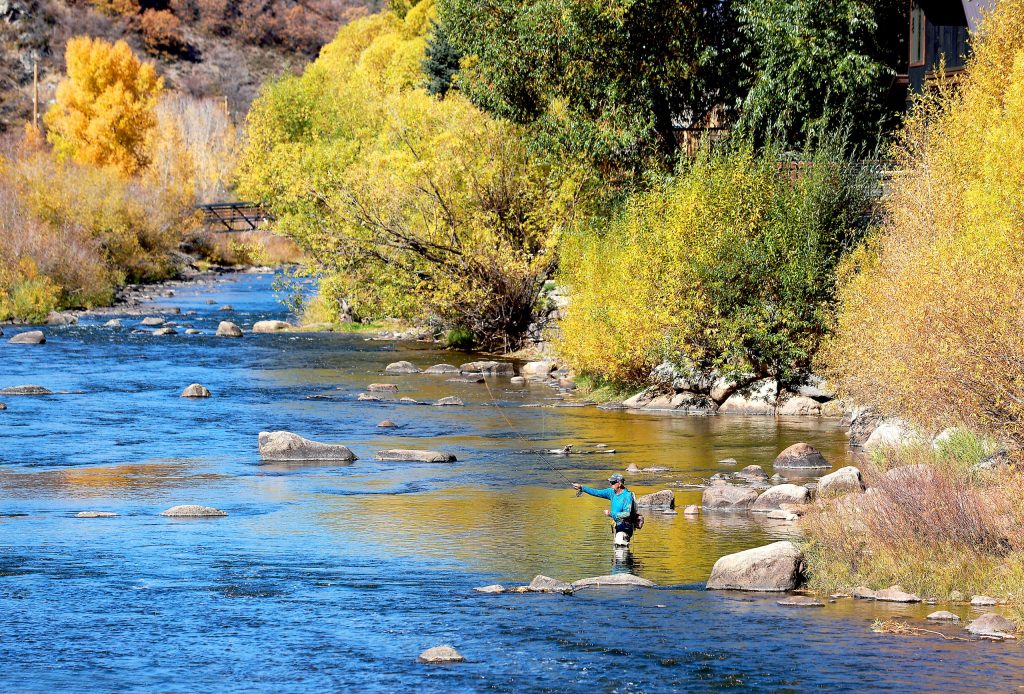

Chris Dillmann/Vail Daily archive

Several Colorado agencies have waded into the discussion of which waters the federal government should protect from pollution and development under the Clean Water Act.

In November, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a change to the federal rule defining “Waters of the United States” or WOTUS to bring it in line with guidance from the Trump administration and a 2024 U.S. Supreme Court decision.

While Colorado girded itself against such federal changes to WOTUS by creating its own guidelines in a 2024 House Bill, Colorado Parks and Wildlife and the Water Quality Control Division of the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment both submitted comments to the proposed rule in January. Despite having state protections, there are concerns with how the proposal could adversely affect arid, Western states and challenge state resources.

Redefining WOTUS

In 1972, federal lawmakers created the Clean Water Act, which protects water quality by setting quality and wastewater standards. It also regulates pollutants and dredge and fill activities such as development and construction in waterways. In the act, protections are afforded to what it calls “Waters of the United States,” which wasn’t strictly defined until a final rule was issued by the U.S. Army Corps and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency several years later.

“The ‘Waters of the United States’ rule matters in Colorado and in any other state, because it determines which waters deserve protection from pollution or industry discharge or construction,” said Sen. Dylan Roberts, D-Frisco. “It’s the baseline determination of which waters receive special consideration versus being able to be polluted without any regulation.”

The definition and rule have been changed many times since the 70s, including at least five times in the last decade in a series of back-and-forth changes during the Obama, Trump and Biden presidential administrations.

In 2023, a Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. Environmental Protection narrowed the definition. This restricted WOTUS to navigable waterways like oceans, rivers and lakes as well as wetlands and “relatively permanent” tributaries that directly connect to them.

The federal Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps began the process in November to change the definition, claiming the proposed changes would bring it into compliance with the Sackett decision and “the Trump administration’s commitment to protect America’s waters while providing the regulatory certainty needed to support our nation’s farmers who feed and fuel the world.”

These changes include redefining which wetlands fit the definition, requiring that waterways must connect to “traditional navigable waters” through a continuous, consistent connection, expanding state and tribal authority, adding the idea of a “wet season” to the definition, and more.

“When it comes to the definition of ‘waters of the United States,’ EPA has an important responsibility to protect water resources while setting clear and practical rules of the road that accelerate economic growth and opportunity,” said Lee Zeldin, administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency in a release. “Democrat administrations have weaponized the definition of navigable waters to seize more power from American farmers, landowners, entrepreneurs and families.”

Mark Squillace, a natural resources law professor at the University of Colorado Law School, said that the Supreme Court’s continued narrowing of the definition — which he said tracks back many years — and the federal rule are “an assault on the law.”

“Specifically, the proposed rules would appear to require that surface waters and wetlands have surface water at least during the ‘wet season’ to qualify for protection, undermining the critical role that these waters play in filtering pollutants and recharging water resources,” Squillace said. “The proposed rule would also remove protections for isolated wetlands and headwaters, thereby increasing the risk of flooding, destroying natural habitats and threatening drinking water supplies.”

“All of this should be understood as a gross violation of Congress’ intent when they passed the original Clean Water Act in 1972,” he added.

Why Colorado stepped in to protect its water

In 2024, Colorado lawmakers stepped in to fill the gaps in protections left by the Supreme Court’s decision in Sackett.

“We anticipated something like what’s happening right now to happen when the U.S. Supreme Court in the Sackett decision essentially removed federal protections for ephemeral streams and wetlands and other types of water in that decision,” said Roberts, who co-sponsored House Bill 1379.

Colorado’s bill was the first of its kind in the U.S. and was afforded relatively bipartisan support, passing unanimously in the Senate and by a healthy margin in the House, Roberts said.

“While this may come across as a partisan issue where it’s flipped from Obama to Trump to Biden to Trump again, in Colorado at least we were able to come together, both sides of the aisle, to say we want to protect these waters in Colorado no matter what happens at the federal level,” Roberts said.

The bill required the state’s Water Quality Control Commission to adopt its own regulations — which it did in December — that protect waterways such as isolated wetlands and seasonal streams without immobilizing construction, agriculture, and infrastructure projects.

“We feel pretty confident that the House Bill 1379 is going to protect the water in Colorado that needs to be protected,” he said. “State law can always be more stringent than federal law, but it can’t be less stringent. So we have every legal basis to put in place our own program after the Sackett decision.”

What Colorado agencies said about the proposal

While Colorado’s waters remain protected by state law, several state departments weighed in on the proposed rule from the federal agencies, expressing concerns that pulling back federal protections of certain waterways will strain already tight state resources and have implications beyond state lines.

At the Monday, Jan. 26, Colorado Water Conservation Board meeting, Matt Nicholl, assistant director for the aquatic wildlife branch of Colorado Parks and Wildlife, said the wildlife agency’s comments “aim to influence national policy” despite Colorado’s “decisive action to secure our own water future.”

Even if Colorado state law protects waters within the states, the reality is that state waters could be impacted by decisions made up and down stream.

“Colorado is a headwaters state that relies on a combination of federal and state regulations to protect water quality for drinking, agriculture, recreation and other uses, both within its borders and for the 19 downstream states that rely on rivers originating in Colorado,” wrote Nicole Rowan, director of the Colorado’s Water Quality Control Division in a submission to the proposed rule. “While Colorado has taken decisive action to protect its waters, the division has significant concerns regarding the proposed rule’s economic impact on the state and our regulated community.”

“Collectively, these waters are physically, chemically and biologically connected to downstream navigable waters, meaning their degradation can significantly impair the integrity of the entire river network,” Rowan added.

Specifically, the division outlines concerns about how the proposal could drastically reduce federal protections for wetlands and streams in arid climates, “severing jurisdiction over reaches upstream” of streams that do not flow year-round or continuously.

Limiting federal protection to waters that flow year-round fails to account for the hydrological differences of an arid Western state like Colorado, where the ups and downs of snowpack and the meltout drive streamflows and water supply, according to Parks and Wildlife’s submission.

“(Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s) comments emphasize that 68% of Colorado stream miles are non-perennial, and a federal shift toward perennial-only protections would abandon the vast majority of our headwaters,” Nicholl said on Monday. “These ephemeral systems are vital for a vast diversity of our terrestrial and aquatic life, including species of greatest conservation need identified in our recent (State Wildlife Action Plan).”

The rule could also mean that Colorado loses federal resources that help with projects and protections in the state.

“The concern with this proposed rule is that now we won’t have any assistance from the federal government in protecting certain waters in Colorado, so it will fall on our state agencies, the Water Quality Control division specifically, to protect these waters, which means they’re gonna need more resources and staff to do that,” Roberts said. “The concern from Colorado’s perspective is not that they’re gonna be able to change our protections, but that we will have the resources to enforce our protections on all of our water.”

The comment period on the rule ended on Jan. 5, sending the process into a review period before the two federal agencies craft a final rule.

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

As a Summit Daily News reader, you make our work possible.

Summit Daily is embarking on a multiyear project to digitize its archives going back to 1989 and make them available to the public in partnership with the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection. The full project is expected to cost about $165,000. All donations made in 2023 will go directly toward this project.

Every contribution, no matter the size, will make a difference.