How a Grand County resident is using collaboration, AI and new tech to help producers dealing with wolves

Wild Ranch is partnering with producers and groups to field test new ideas for mitigating wolf-livestock conflict in Steamboat Springs, North Park and more

Chip Isenhart/WildRanch.org

At the surface, Colorado’s wolf program can appear rife with conflict. However, many Coloradans are working to bridge gaps between the Front Range and Western Slope, ranchers and wolf advocates, and to reduce conflict between livestock and wolves.

Take Chip Isenhart, and his burgeoning organization Wild Ranch.

Isenhart grew up on the Front Range in Englewood enjoying all things Colorado: camping, hunting, fishing and recreating. During the pandemic, Isenhart and his wife, Jill, moved to Fraser. The Isenharts run a conservation education company, ECOS Communications, that designs exhibits for museums and visitor centers, including the Headwaters River Journey exhibit at the Headwaters Center in Winter Park and interpretive exhibits for the town of Vail’s Welcome Center.

And when — months after Colorado dropped the first 10 wolves off in Grand and Summit counties — conflict between the Copper Creek pack and Middle Park producers intensified close to home, Isenhart saw only the potential for solutions.

“We work with a lot of sensors in our interpretive exhibit work, so that when somebody comes into a room, the lighting changes or a monitor turns on or sounds pick up or movement across screens can be tracked by where their feet are in the room, those types of things,” Isenhart said. “I thought to myself, ‘Why couldn’t somebody put a sensor on a cow to detect by proxy what the wolf is doing?’ It’s kind of like putting an Apple Watch on a cow.”

Isenhart pushed this idea out via a white paper to conservation and agriculture experts and practitioners, and the interest eventually snowballed into Wild Ranch.

“When I started Wild Ranch, after I had reviewers looking at this white paper, I really thought that I was going to be working more in line with my skills at ECOS, as somebody who can raise awareness and appreciation and move someone like that to take action,” Isenhart said. “What I realized was that the tools, the non-lethal tools that are available haven’t changed hugely since Yellowstone 30 years ago with wolf reintroduction there.”

The long-term vision for Wild Ranch remains rooted in Isenhart’s conservation education mentality, with the goal of creating opportunities for members of the public to crowdfund non-lethal tools and directly support ranchers’ efforts on the ground. However, in order to have ideas worth funding, Isenhart and Wild Ranch have started to seek out, test and develop emerging technologies and ideas that aim to reduce conflict between wolves and livestock.

“I don’t need to be the one coming up with these ideas, oftentimes, I’m just hunting out there to see what’s new and what I can find,” Isenhart said, likening it to how a bird dog leads the way in a hunt.

This has led the organization to partner with companies like Wildlife Protection Services, a Golden-based nonprofit developing technologies to protect endangered species and ecosystems, and EarthRanger, a software company that integrates wildlife and animal data in a unified platform, as well as with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services on its work surrounding livestock guardian dogs in Colorado.

In addition to testing and pilot programs with producers in northwest Colorado, it’s also taken Isenhart to northern Germany, where Isenhart trained and worked with partners to test artificial intelligence cameras and deterrents that aim to reduce chronic wolf depredations on livestock.

Today, Wild Ranch is in various stages of testing with a number of concepts:

- Solar and satellite tracking collars for livestock guardian dogs

- A “rapid assistance dog team,” comprised of specialized livestock guardian dogs that can be deployed with handlers to patrol “hot spots” of livestock and predator activity

- Tracking and biometric livestock tags that monitor cattle behavior, which can alert ranchers to predator behavior

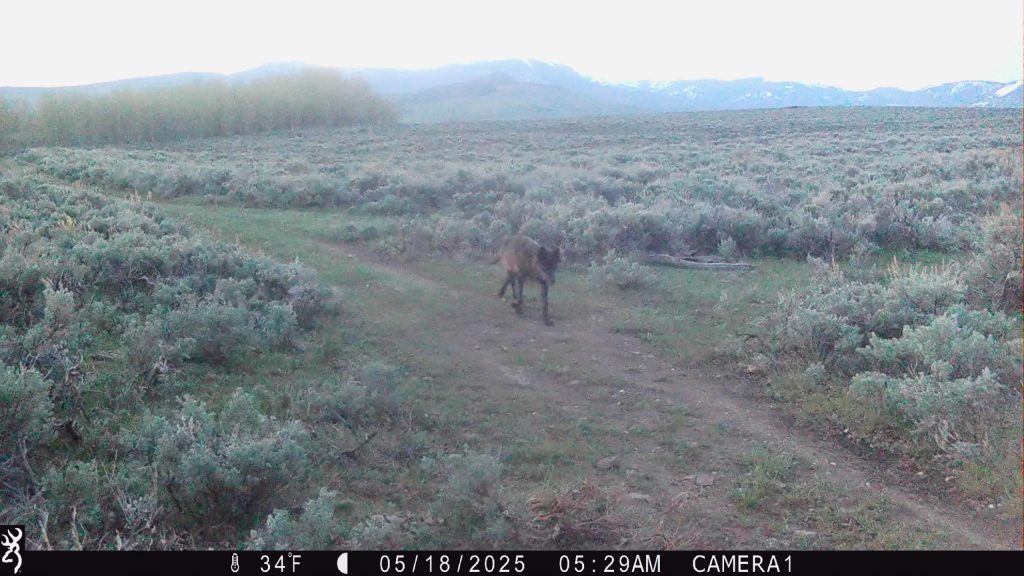

- Artificial intelligence camera traps that can detect and identify predators, then automatically deploy a variety of scare devices

- A “hot spot surveillance and management system” that integrates a variety of technologies and deterrents including livestock tracking tags, automated camera traps and deterrents and more

- An institute for predator conflict innovation, which Wild Ranch describes as “part think tank and global repository of ideas and tools for practitioners, part research/testing and grant making, and part training/outreach,” called “Moonshot Predator Project”

Field testing two new prototypes in North Park

Adam VanValkenburg, a fourth generation rancher in North Park, has been dealing with wolves since before Colorado began the voter-mandated reintroduction in December 2023. VanValkenburg reports having wolf activity around his calf-cow operation as early as 2020, when Jackson County became home to a breeding pair that moved south from Wyoming. The latest activity has come primarily from the One Ear Pack, which he said denned less than two miles from his house, with the last report of activity coming on New Year’s Eve.

“We’ve had wolves here on the landscape for three years consistently,” VanValkenburg said. “And now that the wolves have developed a liking to our area and it is going to be a problem for the foreseeable future, we’re trying to get innovative and stay ahead of the game.”

When it comes to nonlethal tools to prevent and minimize conflict with wolves, VanValkenburg said “we’ve thrown everything at them but the kitchen sink,” listing tools like turbo fladry (a temporary, electric fence with bright-colored flags), critter getters and game cameras.

The challenge is not only that wolves, over other predators that ranchers live alongside on the Western Slope, are incredibly persistent and each livestock operation is unique, VanValkenburg said.

“There’s no silver bullet, no real cookie-cutter solution for nonlethal. It’s so custom-tailored to each operation,” he said.

For example, while fladry has some downsides — including a six-week window of effectiveness, limited supply and maintenance requirements to guard against high winds or migrating elk herds — VanValkenburg called it the most effective tool they’ve used.

“We’re not a very big operation and all of our livestock, houses, buildings, dogs, everything is within that turbo fladry boundary during calving season,” he said. “You go to the neighbor across the fence and it’s not even an option for him and how his operation works.”

Finding effective nonlethal solutions comes down to “trying to get on the forefront, get ahead of (the wolves) a little bit and figure out what works best, what doesn’t and what we need to focus our energy on during the calving season and summer months,” VanValkenburg said.

These summer months, he noted, present unique challenges in Colorado, with few options available to mitigate conflict when the cattle take to pastures he described as “pretty rough, high alpine country” that is only accessible by foot or horseback in some areas.

So, when Isenhart came to VanValkenburg with an idea to trial some emerging technologies that could provide solutions for summer ranges, he was eager to participate. In summer 2025, the North Park ranch became a proving ground for two prototypes that Wild Ranch is testing: the AI camera traps with automated scare devices and the livestock tracking ear tags.

Deploying the scare device system in Colorado is part of a partnership with Wildlife Protective Solutions and Wild Ranch. The system leverages cameras and artificial intelligence to detect and identify the presence of a wolf — or other predator — and then automatically triggers deterrents such as strobe lights, human scent dispensers or soundtracks. In one instance, a large black bear was scared away from a herd of cattle after a speaker played a President Trump impersonation.

“What intrigued me about that is that you don’t have to be there,” VanValkenburg said. “If wolves are in the area and they set off one of those scare boxes, it creates a negative interaction that keeps them on their toes, makes them feel uncomfortable in that area and hopefully keeps them moving on.”

The ranch also trialed two kinds of ear tags, which allowed them to track the cattle’s locations and biometrics. Not only do they send a mortality alert when an animal dies — which could be useful in finding carcasses quickly in the High Country and in identifying whether wolf depredations have occurred — but it sends high-activity alerts that could indicate the presence of a predator.

“If the cattle are moving a lot more than what is deemed necessary by the ear tag, then it will send me an alert and we’ll go out and see what the situation is, why they’re more active,” VanValkenburg said, adding that it has benefits beyond dealing with predators.

“One of the features of both of those ear tags was it creates a heat map,” he said. “It shows you where the cattle are congregating more. So it allowed us to go to that landscape and see what’s drawn them into that location. Is it water? Is it clover? Is it better feed? Is it anything along those lines that could help us in a land management situation?”

The mapping and alerting is made possible through an app called EarthRanger. The company’s engineers created custom alerts for Wild Ranch.

While the prototyping work was challenging and included a lot of glitches and problem-solving, VanValkenburg said he plans to continue the testing work with Wild Ranch and Isenhart this summer.

“It was not for the faint of heart, but moving forward, I’m really optimistic this year with getting those issues ironed out and having more of a dependable situation,” he said.

The scare device system is currently receiving updates that will allow producers to change via software where and when the deterrents are being deployed, which Isenhart called “a huge step forward because, frankly, wolves are probably the smartest, most resilient, large predator in the world.”

“It’s super important to have a very flexible system that can keep these wolves on their toes,” he added. “We have found that it’s a burden on ranchers to have to change that up by actually going out and flipping switches and plugging in a speaker, etc. So we’re aiming for a package where all of that can be changed and monitored remotely so that we have a better chance of really deterring these wolves and having that be a durable result.”

The eventual goal is to combine these hardware and software tools into what Isenhart is calling a “Wolf Hotspot Response Kit” with the goal of creating a more coordinated and flexible response.

“It’s an amazingly positive time of convergence on many tech fronts — increased satellite access and affordability, miniaturization, battery improvements, drones, robots, etc.” Isenhart said. “The advanced systems and Earth Ranger analyzers that allow multiple livestock GPS tags to alert when a herd is running, or bunching up, literally happened in the last two months.”

“We can now combine those alerts with wolf collar data, range rider patrol tracks, automatic scare devices, ultrasonic deterrents and more — all integrated within a secure portal with sophisticated layers of permissions for incident command and communications,” he said.

Creating a new ‘biofence’ against wolves

Nearby, in Steamboat Springs, Wild Ranch is working alongside Pat and Jan Stanko to pilot another idea. The Stankos run Emerald Mtn. Ranch, which not only raises cattle, poultry and sheep, but raises and trains livestock protection dogs. Starting in 2024, the couple became a supplier of Turkish boz shepherds through a USDA Wildlife Service’s program that matches Colorado producers to guardian dogs.

These dogs are bred and trained to stick with and defend herds and flocks of animals, adding an extra set of eyes and protection for ranchers against predators.

Like all non-lethal tools, owning livestock guardian dogs is not for every situation or producer. Training the animals requires significant energy, attention and time.

“Livestock guardian dogs are definitely not a quick solution,” said Jan Stanko. “That’s why we’re trying to plan this RAD team, to see if maybe they could come in if there was an emergency situation.”

This idea between Wild Ranch and the Stankos is to create a Rapid Assistance Dog, or RAD, team, which they describe as a “highly trained, mobile group of guardian dogs and handlers who can be deployed to livestock-predator conflict ‘hot spots,’ offering producers nonlethal support when they need it most,” in an information sheet provided by the Stankos.

While livestock guardian dogs are typically bonded to a specific herd or property, the concept would test whether a pack of dogs could be bonded to their handlers and deployed to “change the behavior of the wolves by just marking, walking around and being a presence,” Pat Stanko said.

Isenhart referred to it as a “biofence,” where the guardian dogs would create a barrier of scents and sounds that deters and disrupts wolves without physical confrontation.

“In our minds, it’s going to be useful in situations where wolves are setting up shop and starting to pick on a couple isolated ranches or producers,” Isenhart said.

They have submitted a proposal for grant funding from the USDA to begin piloting the program this summer. From there, the plan is to spend the next several years developing, testing and adapting the idea, meaning actual deployment could be years away.

“It’s something that’s going to take a few years to get there because it really takes the dogs two years to mature to be formidable and know what they’re doing,” said Jan Stanko.

Isenhart said he is also on a team hoping to design new “smart” collars for livestock dogs through USDA WIldlife Services, which could track the dogs’ behavior and location more efficiently.

How ground work with nonprofits is bridging divides

When Isenhart first started down the road of nonlethal tools, his goal was to bridge the gap between the Front Range and Western Slope when it comes to wolves.

“It’s such a polarized issue because wolves, according to ranchers on the West Slope, have been forced upon them,” Isenhart said. “The (Proposition 114) vote was very close but fairly clean along the East Slope and West Slope, and that tension bubbles up to this day.”

Bridging this is still part of Wild Ranch’s long-term vision, which would see an opportunity for wolf advocates or individuals on the Front Range to “get some skin in the game,” providing money to enable new tools and more effective conflict management for those most affected on the Western Slope.

With the livestock guardian dog team, Isenhart sees an opportunity for individuals to “adopt” or sponsor a dog, providing funding for that work. For other tools, he hopes to find ways for individuals to help pay directly for things like range rider insurance policies or thermal imaging binoculars.

“There’s a lot of projects in the works that would allow folks to microfinance these new tools in a way that would be more rewarding and directly connecting for them,” Isenhart said. “In my work with ECOS, I found the more specific the project can be and the more directly linked to a conservation cause and the people that are embedded within that conservation story, the more success that we’ve had.”

Wild Ranch received seed funding for some of its testing work last year from Rocky Mountain Wolf Project, which is a nonprofit group behind Colorado’s wolf reintroduction.

“Fostering social tolerance is really going to determine the fate and future of wolves in Colorado,” said Courtney Vail, chair of the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project.

Vail said that since wolf reintroduction began, she has focused on “developing relationships with ranchers, trying to listen and be part of the solution rather than the problem and encouraging early adoption of some of the tools and technologies that are available.”

With Wild Ranch, Vail sees not only the opportunity to support the organization’s work in developing an effective package of nonlethal tools, but also to focus on solutions and human connection rather than conflict.

“We need to see collaboration on the ground, these technological innovations that are made readily available to producers, and then to continue to extend the support from all stakeholders, recognizing that producers are bearing some of the burden here, but we’re hoping to reduce that burden through making these tools available, listening and building a support network for them,” Vail said. “I’m encouraged by (Wild Ranch’s) work, and we hope to continue to support it.”

With Colorado Parks and Wildlife often stuck in the middle when it comes to wolves, “these nonprofit groups and individuals that are in it for the long haul are able to fill in the gaps for where the agency either doesn’t have capacity or doesn’t have the resources,” she added.

In just the last year, Isenhart reports having come up with “a lot of promising tools and strategies” alongside partners, however, funding and resources are tight.

“I’ve presented all this to (Parks and Wildlife), but it sounds like the chances for them funding even a hot spot simulation are slim to none, as all their 2026 funds (from the Born to Be License Plate) are going into range riding, or so I hear,” Isenhart said. “Bottom line, funding is super tight. I still don’t know how I’ll even keep covering hard costs with my producer partners next season, let alone afford to keep developing new tools or testing advanced scenarios and systems.”

With this, Isenhart sees the opportunity not only for microfinancing, but for private philanthropy to step up and fill in the gaps.

“If wolves were instead a fungus on corn or some major crop, I bet significant smart ag resources would have been allocated, and we would have come a long way towards figuring this out by now,” he said. “But so far, small livestock producers, along with their important ecological, scenic and even recreational assets are left hanging in the balance, for all of us.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

As a Summit Daily News reader, you make our work possible.

Summit Daily is embarking on a multiyear project to digitize its archives going back to 1989 and make them available to the public in partnership with the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection. The full project is expected to cost about $165,000. All donations made in 2023 will go directly toward this project.

Every contribution, no matter the size, will make a difference.